In the pathophysiology of Sickle cell anemia or Sickle cell disease (SCD), we learn

Continue reading

…creating a healthy world

In the pathophysiology of Sickle cell anemia or Sickle cell disease (SCD), we learn

Continue reading

The pathophysiology of scabies is worthwhile and everyone ought to know the cardinal symptoms

Continue reading

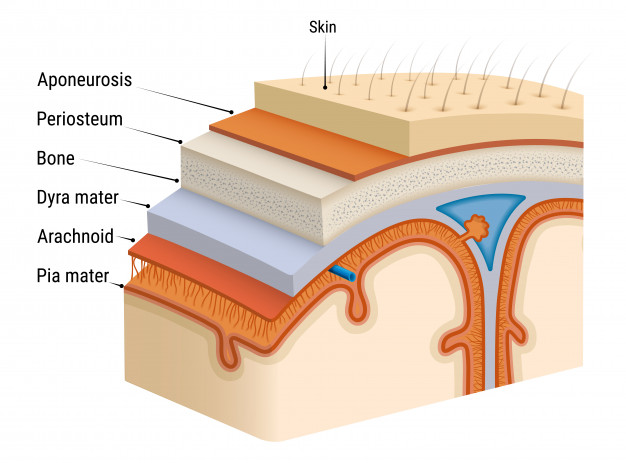

let’s take a look at Meningitis pathophysiology and other essential things for a better

Continue reading

Let’s take a look t the pathophysiology of HIV and the important facts to

Continue reading

The pathophysiology of Syphilis is worth knowing, and a great concern for many in

Continue reading

The pathophysiology of chlamydia comes with many questions, and in this article, it will

Continue reading